I led an in-house workshop last week for UX content folks from Fidelity Investments focused on content portfolios. It was a fun and challenging opportunity to distill my guidance on the topic since starting Content Career Accelerator into a single 90-minute session.

The audience was engaged from the jump — a testament to their welcoming and open-minded energy, and also to the importance of the topic for UX content professionals. In my experience, it’s rare for a company to invest any resources in helping designers with portfolios, let alone their content folks. We just don’t talk about it enough. So it was pretty cool to get to share with 50-odd folks all from the same company!

Portfolio challenges for writerly sorts of people are legion. Feeling like you’re not visually-inclined, or not having visually-compelling aspects of your work to include. Difficulty articulating your contributions within the context of the larger design. Some of your work being ephemeral, such as the very important work of talking people out of doing stupid things with content. I could go on.

There are better and worse tactics for tackling those challenges, and everyone’s portfolio will necessarily be different given their skillset, work history, project history, visual design aptitude, storytelling prowess, and the types of roles they’re applying for. But there are a few things — four, in fact — that every portfolio needs to include, regardless of what you’ve worked on.

So what should you include in your portfolio? Why, what every little boy and girl dreams of having, of course: a pony. 🐴

The P.O.N.Y. Framework

P.O.N.Y. is an acronym to help you remember four things that need to come through clearly in your portfolio. They are:

- Process: How you did what you did. (Your process, not the process.)

- Outcomes: What actually happened.

- Narrative: The “so what”, in the form of a coherent and compelling story.

- You: Personality, perspective, and philosophy.

Unlike STAR, for instance, P.O.N.Y. isn’t telling you the order to put things in. It’s more of a shopping list to help you make sure you’ve got everything you need. (And you can still use STAR or other methods to shape your narrative.)

Why It Works

P.O.N.Y. describes the ingredients necessary to tell a work story worth including in your portfolio. If you can tell a story about what happened, the process you used, and the outcome that was achieved in a way that says something about you — who you are as a writer, or designer, or strategist, or manager, or teammate, etc. — then you can put it in your portfolio.

Content work often involves relationship and stakeholder management, conversations and negotiations, independent research, and collaborations that go far beyond what most product people think of as “cross-functional”. That kind of work can be difficult to describe when you’re trying to follow some sort of UX design case study template.

And even if you are presenting a more traditional case study, P.O.N.Y. helps ensure that the reader can see you within that larger story and why that story matters, which is important given that it’s, you know, your portfolio.

(Work stories, by the way, are just stories anyone can tell about a good piece of work they did in a past role, whether or not that work involved slick-looking wireframes or complex journey maps. It’s provides an alternative to the case study mindset that gets a lot of people tied up in knots — especially if they aren’t working at a level where they get to own the strategy and lead an entire end-to-end initiative.)

P = Process

As I’m fond of saying, there’s more to writing than writing. A good way to improve as a writer (and as a designer and strategist, for that matter), is to notice your process: be mindful of what you’re doing while you’re doing it, and intentional about why you are doing it.

Noticing your process empowers you to describe that process. Which is your process, independent of a larger product or UX design process. The person reading your portfolio already knows about the Double Diamond, or how a website redesign or content audit tends to go. They want to hear about how you work:

- How did you plan your work? How did you stay on track with it?

- Where did you start? Why?

- What tools and methods did you use? Why did you use them?

- What constraints shaped your approach?

- Whom did you involve or get feedback from, and why? What did you do with that feedback?

- What happened along the way? Did you have to change your approach at all? Any false starts? How did you identify them?

- What conversations did you have along the way? With whom? To what end?

- When did you ask for help?

- What research did you have to do? Did you learn or try any new tools or techniques?

- How did you evolve the fidelity of your work? Were there early drafts and later drafts? Preliminary decisions before final alignment?

And so on. Not all of those questions will have interesting answers for a given story. The important thing is to look closely at how you did what you did. Hiring managers want to know that you know what you’re doing, and that you’re doing it intentionally. Focusing on process makes that apparent to readers regardless of their familiarity with content strategy, content design, and all of their friends.

Exercise: Describe your process.

Grab pen and paper. Think about a recent content task you were part of — whether that’s revising an error message, designing a transactional email, auditing a section of content; anything!

List out every single step you can think of from the beginning to the end of that process. Be wildly detailed. Some examples:

- Started a new document.

- Reviewed existing experience.

- Wrote five variations of the headline.

- Outlined copy with bullet points.

- Messaged fellow writer for feedback on word choice.

Put in every step you can think of. (If you were describing the making of a PB&J sandwich, for instance, you wouldn’t want to forget “open bread bag”, “remove two slices of bread”, and “place bread on plate”.)

Highlight or star a few steps that didn’t occur to you before this exercise, or that strike you as something you might do differently than other practitioners. That’s a good start for your story!

O = Outcomes

Outcomes are what happened as a result of your involvement in the work. They are distinct from the outputs of your work, which might be tangible deliverables like writing, presentations, and reports, or ephemeral outputs like conversations.

You want to focus on the outcomes of your own work and activities in the particular because you may not have control over the larger project outcomes — maybe the project got axed and never shipped, or engineering ran into a wall and had to hack away at the MVP, or a competitor beat you to the punch, or an executive made some “improvements” to your writing six months after your last involvement.

Questions to help you identify outcomes include:

- What’s different now, as a result of my contributions?

- What’s better now, as a result of my contributions?

- What’s possible now, that wasn’t possible before, as a result of my contributions?

- What choices did we make, or not make, as a result of my contributions?

- What potential negative outcomes were avoided as a result of my work?

The outcomes of your work don’t have to be limited to the user experience itself. Content work is often a force multiplier, making other people and teams more efficient and successful. Example outcomes for a content professional could include:

- Reduced number of touchpoints needed with engineering to finalize copy, enabling them to focus more and deliver faster.

- Enabled UX design partner to support an additional squad, reducing the need for increased UXD headcount.

- Identified and eliminated ambiguity in description of pricing plan in collaboration with legal team, reducing our risk.

- Reduced number of customer service inquiries about topic by 12% compared to previous year.

If you made the experience better, by all means, talk about it! But be sure to also look beyond what ships at your impact on your team and in your organization.

N = Narrative

Portfolios are for presenting. The N in P.O.N.Y., narrative, is a reminder to put your pieces together in the form of a story.

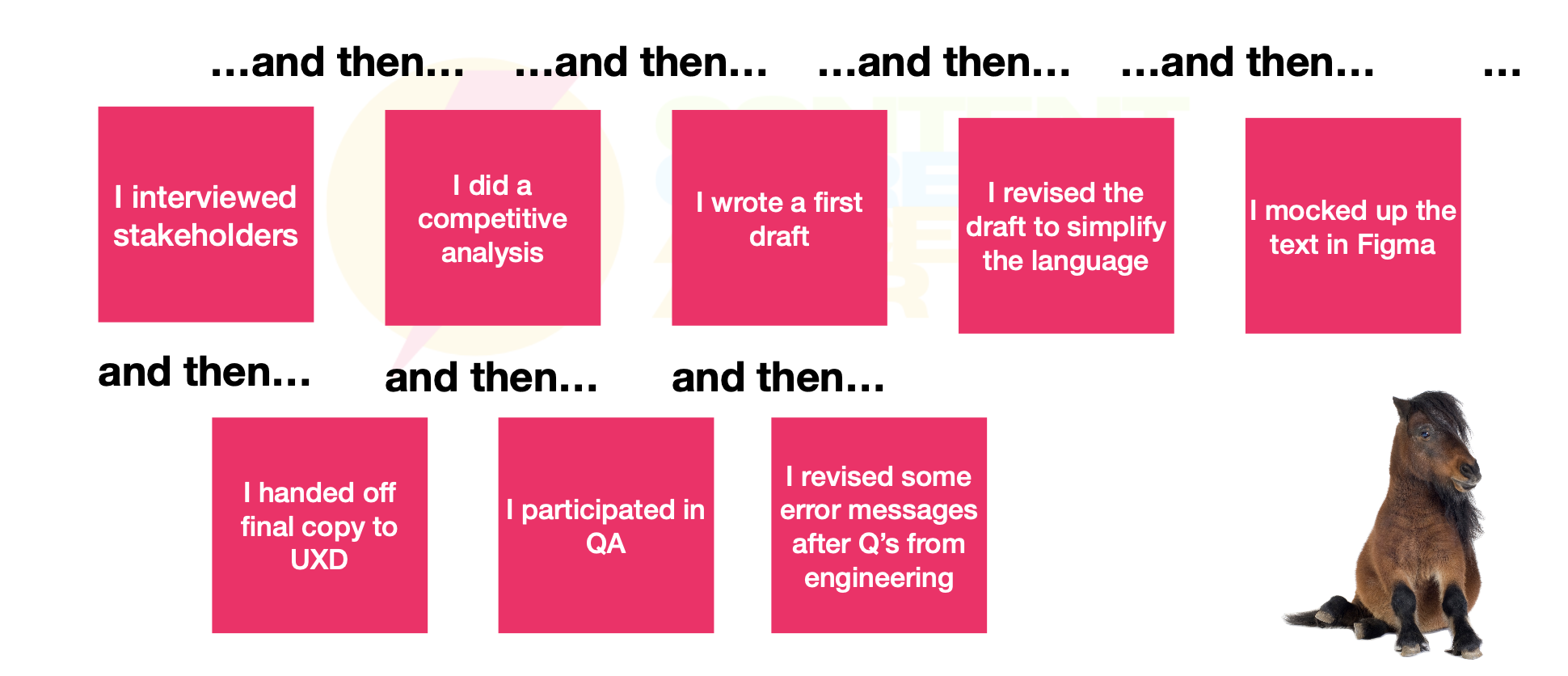

We had a kickoff meeting and then we did a competitive analysis and then we looked at the analytics and then we talked to the SMEs and then…

That’s not a narrative, that’s just stuff that happened.

Fiction writers, especially screenwriters, sometimes organize their stories in “beats”. Beats are individual moments or happenings within the narrative, that you can shuffle and play with to find an arrangement that creates a compelling and propulsive narrative. These identifiable beats, which form the pulse of your narrative, are often absent from portfolios, especially web-based portfolios that afford long lists and dense paragraphs.

Using presentation software like Keynote or Google Slides encourages organizing your story in beats, and will make it easier for you to play with your structure — slides tend to be easier to move around than sentences and paragraphs.

One of my favorite tools for evaluating the quality of your narrative is from this video featuring Trey Parker and Matt Stone, the creators of South Park. Say what you will about their sense of humor, but you can’t argue that Trey and Matt aren’t prolific; 300+ episodes of South Park and counting, not to mention underrated (IMHO) movie gems like Baseketball and Cannibal: The Musical (not for kids, obviously.). Not everything they’ve done has made me laugh, but rarely has it ever made me feel lost or bored, either.

As Matt and Trey explain it, a small child ties stories together with “and then”.

We went to the park and then I saw a dog and then I went down the slide and then there was a rock in my shoe and then we picked dandelions and then the dog barked real loud and then I saw Billy and then the squirrel was in the tree…

Sound familiar?

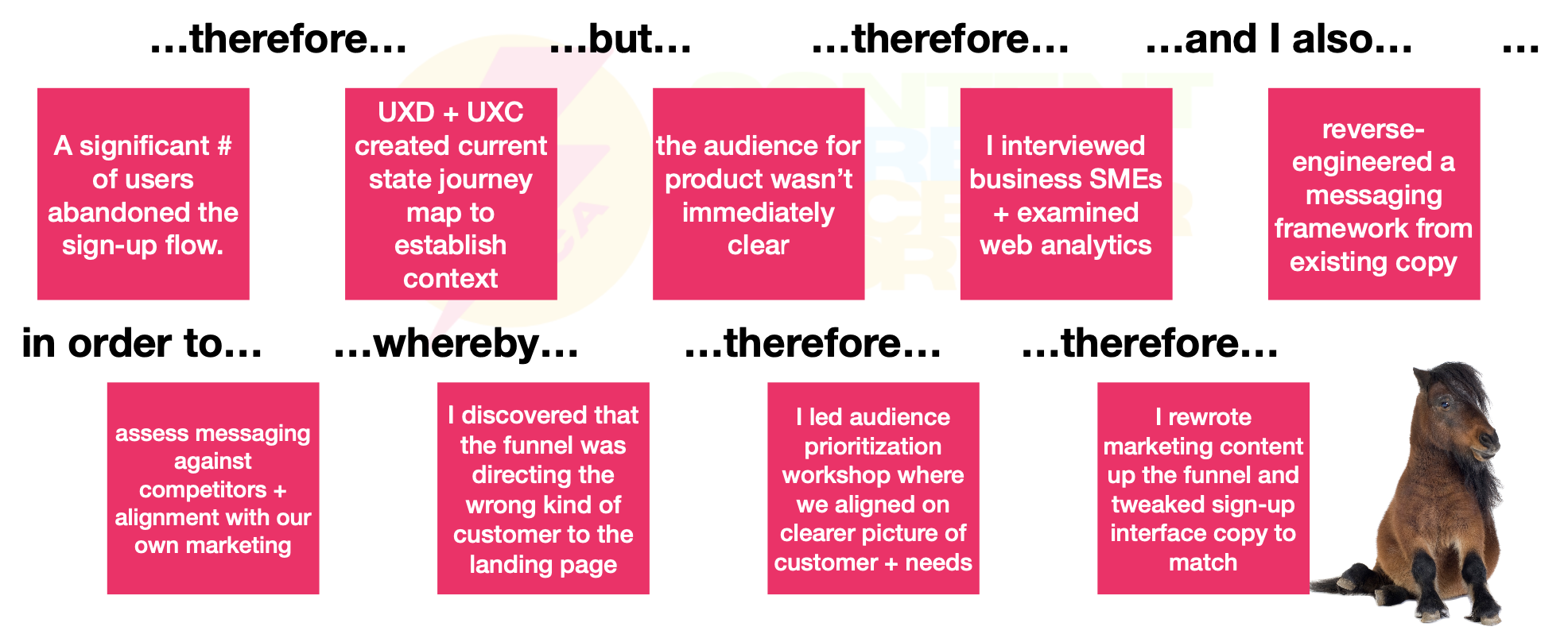

Matt and Trey instead recommend connecting your beats with therefore and but. These are great connectors for work stories. They suggest rationale — the why behind what happens next.

A content therefore might be something like:

Interviews revealed that customers were unfamiliar with the technical language of investing, therefore I created a word list and writer’s guide that provided designers and writers with plain-language alternatives.

And a content but (hehe, content butt) might be something like:

We attempted to give informed consent about how their email address would be used in the mobile app onboarding experience, but found that there was simply not enough room to accommodate it. Therefore, the UXD and I sat down together to imagine a new sign-up journey that would be just as efficient but include easy-to-find off-ramps for users who desired more information.

Here are some contrasting examples I shared during the workshop:

UX work stories and case studies are sometimes more complicated than a South Park episode, so you may need to use other implied connections between your slides; the occasional in order to, also, or whereby should be fine, so long as you’re not using them to sneak in an and then.

Y = You

People hire people, not portfolios.

The above sections already make clear that you need to center your work, contributions, and impact in the stories you tell in your portfolio.

But your portfolio is not just about your work history and experience. It’s also about you — as a writer, as a designer, as a teammate, as a mentor … as a person.

So I encourage you to find sensible ways to personalize and showcase your personality with your portfolio. Remember that your readers/audience are human beings, and consider saying hello to them. Share something from your life, or your friendly smiling face. Describe the philosophy that informs your work overall, or a perspective you were able to bring to a given project that draws from your personal experience.

Take ownership of your stories, and tell them from your point-of-view. Acknowledge the ups and downs, the roadblocks and frustrations, the wins and celebrations. Be a person!

Exercise: Put yourself in the headlines.

If you’ve never heard of Valar, Maiar, or the Silmarils, but you have heard of Bilbo, Frodo, or Gandalf, you might know where I’m going with this. Tolkien didn’t introduce us to his fantasy universe from the top down. He started with one small tale of one literally small creature: Bilbo Baggins, The Hobbit. You may have been part of the most important quest in your company’s history, but you were still just one little hobbit. We want to hear your story, not the story.

The titles you give to your work stories and case studies are your first opportunity to frame the story from your perspective.

- Organizational frame: Patient Portal Redesign

- Individual frame: Reducing stress for patients and families with plain language

- Product frame: Neo-Bank Account Onboarding Flow

- Individual frame: Making investment concepts accessible in a mobile experience

- Design team frame: Customer pain point research

- Individual (hero) frame: Identifying untapped revenue opportunities through customer research

Take a look at your existing portfolio, or jot down a few work story ideas. Try rewriting them to put yourself at the center of the story.

Try it out!

Put the PONY to work on your next portfolio piece, or use it to revise an existing draft, and let me know how it goes!